Postmodernism in Nepali Literature: A Theoretical Mismatch

- Mahesh Paudyal

Without being burdened by the imperatives of defining

categories—as those related with ‘postmodernism’ are terms overwrought by

discussions across the academia all the world over and are conceptually

indefinable—this paper claims that there is no overtly visible and identifiable

symptom in Nepali literature that is strictly postmodern, though in painting,

music, films and fashion, one could probably make a tally of things, both

structurally and thematically, and make a table of the postmodern. Postmodern

is not something that conforms to strict bracketable traits; rather, it

encompasses many things at once, and therefore, is plural.

There are many postmodernisms, and different authorities of

the theoretical conundrum position themselves on different ends of the same

thing, sometimes even to the degree that they contradict one another, and

nullify the whole attempt to define. In fact, postmodernism sprang from the

debates about finalities, and sought to jeopardize any attempt towards

finalizing, normalizing, stabilizing, defining, fixing, coding, symbolizing,

classifying and universalizing a concept or a code. Still, for a purpose Spivak

might call ‘strategic essentialism’, we might tacitly agree upon a few trends

that have been recognized as postmodern, and see if Nepali literature—whose one

facet has been claimed as postmodern by certain critics of late—qualifies to that

rank.

One important irritant persistently creeping into any

theoretical discussion about modernism or postmodernism is history.

The discipline is so pervasively and so intricately connected with politics

that it cannot be done away with, when literature is discussed, both in

relation to modernism or postmodernism. Besides this, history is an indefinite

repository of meta-narratives and grand-narratives, and hence its inevitable

relation with modernism and postmodernism is quite self-evident. Modernism was necessarily about

criticizing history and seeking a break from it—a move away from history’s

totalizing and centralizing impact towards individual self-awareness, and

therefore, away from institutional identities towards individual identities.

History—along with religion at its core—as modernism depicts, was an eclipse

that cast a heavy shadow of pessimism, fragmentation, hopelessness, spiritual

banality, loss of faith in politics, religion, and God, resulting into a

conditional continuation of faith in science and reason. For postmodernism,

history is an epoch of the past to be objectively alluded to— neither to

criticize nor to eulogize—but to present it in a form different from the one

presented by the traditional, nationalistic historiography and to lay bare

paradoxes and contradictions within itself, so that it looks altogether

different and multiple. Krishna Dharabasi’s Radha[1] which

deconstructs the traditional Radha-Krishna binary could be a case in point, but

it alone doesn’t make up an example of postmodernism in Nepali fiction simply

because of its feministic bias, which creates another set of binaries. Nabaraj

Lamsal’s Karna[2],

which topples the meta-narrative of the Mahabharata in

relation with its depiction of Karna as villain is interesting

and calls for a confused attention whether it is a postmodern experiment, but

the author’s bias—which the postmodernists would never show—is very

apparent, and hence, the epic, both in form and content, is still modern.

Jagdish Ghimire’s Sakas[3] is

apparently too critical of history and deals more with its psychological

impacts than the structure of history itself, and therefore, continues to be an

example of a modern text.

It will be a beneficial idea to continue the discussion by

considering the very term postmodernism as a tripartite: post-modern-ism, as

Eva T.H. Brann suggests[4].

‘Ism’ as she claims, is “running in droves” and for this, we must locate a

whole group of writers—not critics who foist incompatible categories—who make

such an ‘ism’ a trait of a group. In case of Nepali literature—be it in poetry,

novel, story or any other genre—the claim is repulsive, because there is no

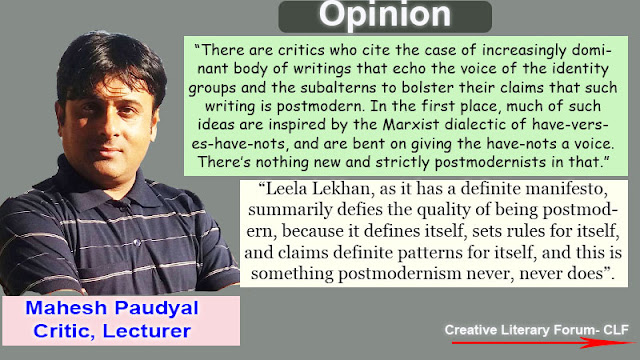

such group. Some critics claim, the practitioners of Leela Lekhan,

a type of writing that sees life as a game with various facets, like the life

of Lord Krishna, are postmodernists. Leela Prastav of Indra

Bahadur Rai and his followers[5],

the does, to a great extent identify its proposal with postmodernist practice,

and writings coming out of the pen of most of these writers do not rigorously

foreground any postmodern ethos. The Prastav is Derridian to a

great extent—as it allows no finality to any interpretations and leaves

everything to a lidless end—and it will be a lame mistake to claim everything

Derridian—which is a linguistic, and strictly speaking semantic idea—with

postmodernism, which is a cultural category. Leela Lekhan, as it

has a definite manifesto, summarily defies the quality of being postmodern,

because it defines itself, sets rules for itself, and claims definite patterns

for itself, and this is something postmodernism never, never does. A postmodern

work, as Leotard[6] contends,

is not composed in accordance with any previous universal rules, or

meta-narrative. This is to say that a postmodern tendency doesn’t rest on a set

manifesto; its traits evolve out of itself, and need not—and does not—conform

to any proposal.

There is (was) a group of poets in the east that incepted in

the 90’s as Rangavadi, and their practice, to a large extent, defiled most set

rules, and sought to identify for itself a unique identity as poets. They even

took up concrete poetic trends, and defiled classical rules and norms for

poetry. Rangavad attempted to see life as a spectrum of colors, and its

different combinations. But by the very name and definition, it has a

structuralist inclination. Moreover, thematically, the group chose issues of

identity and recognition, and picked characters from the lower strata of life,

therefore making their positions more akin to structuralist Marxists, and not

sustainably postmodern. There is no other group identifiable in Nepali

literature which has practiced a sustained exercise of literary endeavor that

qualifies to the rank of ‘ism’, and is still identifiably postmodern. A few

authors tried something called ‘mixism’—a name neither theoretically accepted,

nor established as an experiment. It was an attempt to mix generic forms of

poetry—ghazal and lyrics—but unlike collage and pastiche that settled down as

identified postmodern experiments—owning mainly because of the fact that its

pioneers could produce their own practitioners and successors—mixism failed to

gain currency, and did not evolve as an ‘ism’. It was aborted before late.

Another test-case is in relation with the prefix ‘-post’ in

postmodernism. Modernism in Nepali literature doesn’t coincide with modernism

in the west. Modernism in the west overlapped with the rise of

industrialization and the maxima that marked the limits of colonial expansion.

It also took along settled polity, established political systems, expanse of

the market, rise of education, and pervasion of market economy. These

parameters are repulsive in Nepal. The latest political questions in our case

is not one of experimentation as is true for it the west. It is more a question

of finding ways to replace the erstwhile feudal set up—represented by the

vestiges of monarchy and landed nobility—by a more egalitarian society. These

are questions America tackled in the 1770s, France also in the 1770s, England

in the second half of the nineteenth century, Russia in the 1920s and China in

the 1950s. This political modernism prepared grounds for their literary

modernism, and now when the modernisms in these countries have matured, it is

obvious that they seek an escape from their own tedious continuity, and so,

postmodernism became inevitable.

But the same is not true for Nepal. The collapse of Ranarchy

in 1950 marked the first most remarkable manifestation of a consciousness for

modernizing. It intended to end and did end and centralizing, closed,

dictatorial, conservative and coercive rule of the Ranas, to be replace by a

better, humane and democratic system. But, since the 1950s, our politics has

not been moving forward; it has just been oscillating between a mean position,

the back-tracking being more apparent than forward swinging of the pendulum.

The most important question the nation was facing back in in 1950 was as to

what kind of polity should replace the Rana oligarchy. The same question loomed

over in 2060, 2071, 2079, 1991, 2005-06, and continues to pose today in 2013:

what kind of polity should replace the past system, and by the same token, the

Rana legacy of dictatorship, feudalism, inequality, and willfulness? Ever

since the question was settled in 1947, for once and (seemingly) forever, India

has moved ahead. We have oscillated, more backtracking than swinging forward.

We have, therefore, failed to cash the most important political event that was

apparently modernist in the sense that it was a show-cashing of the highest

degree of consciousness, something like what Kant called a freedom from

‘self-incurred tutelage’ for enlightenment. All political movements in Nepal

since 1950 are nothing but newer versions of the same thing; just a revised

echo of the 1950 revolution. Even by claiming that we are exploring the

possibility of federal system doesn’t confer upon us a title of the postmodern.

This was a question most Asian and African nations dealt with, long before the

onset of modernism, or almost during the time we have identified as modern.

This is, at least, a step towards modernizing ourselves.

If modernism in literature is to be seen in connection with

the ground reality of the country and not just as a disjoint category called

consciousness—this the Marxist might refute as impossible—Nepal is

still struggling to achieve a good shape of modernism. Accepting literature as

realistic depiction of the fact supplies us the reason that ‘fact’ in today’s

Nepal is pre-modern. I am aware, that in urban spaces like Kathmandu and

Pokhara, due largely to the expanse of media and direct interaction with the

western culture, symptoms of change are traceable, but literature—if it has to

be Nepali literature in strict sense of the word—cannot behave as an island by

neglecting the voice of the 70 percent of the nation’s population, which facts

claim with authority, is living in a pre-modern situation. We are still seeking

to define our political system. The fundamental question, still, is to replace

the economically stratified society strewn with untellable inequality by an

egalitarian equation, to ensure the minimum rights of women and children, to

allow roads to every village, to manage an uninterrupted supply of power to

every household, to manage rice in remote districts of Mugu, Humla and Kalikot,

to supply pills to the victims of diarrhea in Jajarkot, to manage text books

for school-going children etc. Even the minimum that makes a country modern has

remained a far cry in our country. How then comes the questions of the

postmodern, unless it is willfully foisted upon an incompatible cultural space

by ambitious critics and reviewer at an incompatible time?

What is plain, therefore, is that like the nation itself,

our literature is struggling more to register its departure between pre-modern

and modern. Since there was no strictly identifiable literary phenomenon that

spark-plugged modernism in Nepali literature, its bracketing within the limits

of time is a question without answer. Critics have identified 1937—the year

first prose poem “Kaviko Gaan” was published by Gopal Prasad Rimal and “Prati”

was written by Laxmi Prasad Devkota[7]—as

the point of departure, but I am of the opinion that a generic form can never

set in motion a new movement in literature. It has to be an epoch-making

political event, or a ground-breaking, edge-cutting, content-determined work of

art—like Joyce’s Ulysses for example—that should make the

limit. Seen this way, real modernism started in Nepal, politically, only in

1950 with the collapse of the Ranarchy, and the exercises to replace it with a

more democratic system has not been achieved even today. Time, therefore, is

not politically ripe, to think of postmodernism in our case. If literature can

divorce with politics and can carve for itself a new trajectory of development,

I am unsure what actually inspires and propels literature. The same is true for

postmodernism, and I agree with Linda Hutcheon: “What I want to call

postmodernism is fundamentally contradictory, resolutely historical, and inescapably

political” (4)[8].

If it is merely ‘imagination’ that matters, we are simultaneously in all ages:

pre-modern, modern, postmodern, and to contain all these at once, we are in

a romantic era, which will last forever, because imagination

will last forever.

There are critics who cite the case of increasingly dominant

body of writings that echo the voice of the identity groups and the subalterns

to bolster their claims that such writing is postmodern. In the first place,

much of such ideas are inspired by the Marxist dialectic of

have-verses-have-nots, and are bent on giving the have-nots a voice. There’s

nothing new and strictly postmodernists in that. The whole premise, if

explained as postmodernist, has the fear of being self-defeating, because in

order to refer to and identify a group, the writer has again and again got to

pull into discussion the existence of another group—allegedly a dominating one,

a bourgeois one—and once again, the structuralists’ favorite binaries figure

out. Postmodern text should, instead, try to dismantle the very premise that

enables such binaries to stand, and theoretically argue that nothing that

defines groups as haves or have-nots, or oppressed or dominant, ever existed.

Postmodernism is never prescriptive; it is merely demonstrative.

As for the subalterns’ claims, nothing save the denouncement

of nationalistic historiography is postmodern, and the whole project—led initially

by Ranajit Guha in India—was pointed out to be neo-nationalistic in the sense

that all that led the project were elites, and the subjectivity of the

subaltern was, in the long run, their invention. The project was, therefore,

plagued by the fact that it contrarily confirmed Spivak’s concern that a

subaltern lacks the infrastructure that allows it a real voice. The same is

true for all writings about the subaltern in Nepal. It has neither questioned

the foundations of binaries, nor developed a methodology markedly different

from nationalistic historiography. A few novels in this line like Taralal

Shrestha’s Sapanako Samadhi and Rajan Mukarung’s Damini

Bheer have dealt with history and juxtaposed the subaltern vis-à-vis

the bourgeois history, but structurally, they reproduce the traditional novel,

and thematically, there is nothing like the nouveau roman—like

Alain Robbie-Grillet’s The Erasers, for example—that questions the

very praxis of the binaries that enable the visibility of the subaltern in comparison

with the elites and the aristocrats. The project, therefore, is not

postmodern.

The last point this essay tackles in relation with the

confused idea of postmodernism relates with the literature of Nepali Diaspora.

In the first place, the theoretical premise in which Diaspora is being confused

with emigrants is pathetically wrong. There is no doubt that a huge chunk of

Nepali population is abroad—most of them for work, and a few naturalized in the

past two decades—but they are emigrants and not Diaspora, because they still

have homes and families here and are likely to return any day. Those

naturalized abroad have an extremely short history out of home, and therefore,

they do not possess the qualities necessary for defining a population as

diasporic—namely a faint memory of the homeland, an ambivalence of conformity,

a situation of cultural hybridity, a difficulty that impedes coming home, an

organized effort to create an imaginary homeland, and an inability to mix with

the host culture, etc. Their children can be diasporic, but they have not

become writers yet. The real Nepali Diaspora are people living from centuries

in North-East India, Bhutan, Burma and some settled ex-army men’s families in

Hong Kong, UK and Brunei. But they either have contributed little to the corpus

of Nepali literature, or, their writing doesn’t show postmodernist trait in an

extent that it inspires a different theoretical classification.

What then is all this fuss about postmodernism in Nepali

literature? Much of it is a confusion, coming out from critics who are not, in

fact, attempting to show postmodernity in any work of art, but are trying to

explain and interpret western postmodernism to their eastern students.

Secondly, there is an anxiety associated with our critics to cash in hand any

fashionable western theory and use it outright, without considering whether the

soil and air here is prepared for that. Third, the confusion of postmodernism

and postmodernist is rampant. Fourth, the tendency to lump every

post-structural experiment as postmodern too is there in our case. All these

points—one to four—are at once prone to questioning by the single fact that

postmodernism tries to locate that the owners of information in the news age

have now changed from institutions to individuals, but in case of Nepal, almost

all the information and knowledge is still controlled or regulated by

institutions—either directly by the state, or private institutions that control

the information technology—and therefore, the postmodern condition is not yet

traceable. The question that our literature reflects a neo-natal category

called postmodernism—at least on our case—is therefore, summarily ruled out.

The best idea, therefore, is to see how Nepal can streamline

and nurtures its own alternative modernity—as projected by Sanjeev Upreti[9].

We need to see if we can combine our nascent modernity with some of the

strengths of the western postmodernity—likes its apologies for pluralism and

liberal humanism—and carve a more defined and matured modernity. We have to

wait and see if more of experimental fictions like those of Kumar

Nagarkoti—gradually moving out of Joycian hangover, though—and poems like those

of Manprasad Subba come and enrich our literature till a formidable body of

work that is postmodern in the real sense becomes traceable. We must wait and

see if the likes of the film A Clockwork Orange Time Bandit or Blade

Runner, or novels like 1984 and novels of Thomas

Pynchon become visible in Nepali literature. Since the possibility is a far cry

as postmodernism is fast dying out and becoming anachronistic, it too will be a

good idea that literature can still do well by foregoing or dispensing with

postmodernism. It is not necessary that we must always subscribe to any idea

that is western. How about making genuine and committed efforts to identify and

define our own type of unique modernism, and free ourselves from the anxiety of

postmodernism? Harold Bloom’s children-of-mind better remain silent; anxiety of

influence is not always a good idea!

A note of caution before I end! There are two groups of

people, who have made postmodernism a buzzword, of late, in Nepal. In the first

group are vehement critics of the phenomenon—most of them being Marxists—who

are inspired by Frederic Jameson’s explanation that postmodernism is the

“cultural logic of late capitalism”[10], and therefore quite coercive. Second group consists of the

enthusiasts of critical theory—most of whom are democrats—who champion the

postmodern claim for multiplicity, and therefore, argue that it can give voice

to the hitherto silenced communities. Both the stands have their strengths, but

are pathetically plagued by sheer limitations. The first group oversees the

idea that postmodernism has vaporized before settling down—even for a brief

spell of time— in Nepal, especially in literature and therefore, their fear is

about a non-existent Sandman. The second group makes up a contingent of

neo-normativists, who want to replace one state of affair—namely, a society

characterized by one group’s hegemony—by another, but they oversee the fact

that by siding with another prescriptive idea, they become positivist, and put

the very notion of postmodernism into question by being prescriptive. I am,

therefore, arguing for a third polemic : postmodernism did not influence Nepali

literature in any apparent fashion, and therefore, it will be the best idea to

explain it away as something that came in the western metropolis, and died out

there itself. Its aftershocks might have reached our thresholds, but has

subsided without leaving any traceable change or damage. What we need to

embellish, at the present, is the idea that our modernity needs maturity, and

we must work in that line for a few more decades, and give a final shape to our

alternative modernity.

Leave a Comment